Why Doesn’t The Government Subsidize Healthy Food? See Answer

First, why doesn’t the government fund healthy food?

By definition, subsidies are intended to lower the cost of producing a good or service. Since fruits and vegetables are naturally inexpensive, the government that subsidizes them would have to cover the entire cost of production. That would be equivalent to purchasing something at Wal-Mart or another grocery store at full price. Not only would it be expensive, but it would also be absurd. Fruits and vegetables would have to be produced at full cost by the government, which would be expensive and ineffective.

For more information, keep reading.

Table of Contents

Why Doesn’t The Government Subsidize Healthy Food?

Because I had my own questions about it, I did a ton of research on the subject. The government does subsidize farms and crops with taxpaying dollars. However, the majority of the subsidies go to wheat, soybeans, and corn, which are used to produce processed food, junk food, and animal products. You are therefore correct in suggesting that perhaps more should be done by the government to assist low-income families. With more fruits, vegetables, and grains, the family members can eat healthier. This isn’t just by choice; it’s also because they’re less expensive and allow for healthier eating on a budget!

Why Fruits, Vegetables Are Excluded From Farm Subsidies?

The producers of fruits and vegetables opposed government subsidies for their products, which is the short answer. We can learn some interesting details about how we got here by looking back at Congressional records from the 1990 Farm Bill.

1990: A “flexible” Farm Bill

The farm bill debate in 1990 focused on whether to allow farmers greater freedom in the crops they choose to plant without endangering their ability to receive farm payments. In the past, a farmer’s eligibility for farm payments depended on his or her “historical planting patterns,” so if they switched to a different crop, they would no longer be eligible.

The idea of “decoupling” payments from production, or allowing a farmer to plant a different crop and still be eligible for payments, generated a lot of debate. The Senate Agriculture Committee rejected an amendment that would have allowed farmers to rotate crops on 25% of their base acres without losing payments or program eligibility, according to a June 14, 1990, Reuters article. Senator Tom Daschle at the time stated, “The problem is not flexibility. Decoupling is the difficulty. From a policy perspective, I believe it to be a serious error.”

Flexible Thinking Is Key

Daschle objected, but the Senate report from July 6, 1990, contained farm bill language that would have given farmers the freedom to plant any crop on 25% of their land without losing base acres that were used to calculate payments.

Farm payments would still be available to producers even if they decided to grow fruits or vegetables on a portion of their property. According to the Agriculture Committee, producers should be free to plant any crop they choose on any amount of land as long as they stay within the allotted acreage limits without losing crop base land.”

In the Senate report from July 18, flexibility was still the vogue: Planting flexibility is important because it allows farmers to produce any combination of crops in response to market signals, said Nebraska senator Bob Kerrey at the time. The ability to rotate crops allows farmers to better conserve soil, safeguard groundwater, and lessen their reliance on fertilizers and herbicides. This makes planting flexibility crucial.”

Decoupling farm payments was supported by those who wanted farmers to be free to respond to market forces and not be forced to grow a particular crop in order to continue qualifying for farm programs.

It’s About Fairnessble

Sen. On July 24, 1990, after the aforementioned Senate reports were released, there must have been a sizable amount of lobbying. In order to prevent some fruits and vegetables from being eligible for the commodity title’s flexibility provisions, William Cohen of Maine proposed an amendment.”

The issue of fairness was a concern for Cohen and other amendment proponents. According to Cohen, it concerns the situation in which those receiving federal assistance are in direct competition with those who are not.”

Sen. Kent Conrad of North Dakota expressed worry that program crop producers with a protected base would switch to growing non-program crops (such as fruits and vegetables) during times of high prices, which would lower prices and negatively affect those growers who rely solely on non-program crops for their livelihood.

A few people opposed the amendment. Sen. Rudy Boschwitz of Minnesota criticized the farm bill for giving farmers contradictory instructions; for instance, one farm bill emphasizes increasing crop production while the next promotes conservation. Boschwitz opposed the Cohen amendment and was strongly opposed to giving farmers less freedom to decide what to plant in response to market forces.

“However, just as we are starting to unlock, this amendment is locking us up once more. The goal of this [farm] bill is not to bind farmers to doing certain things, said Boschwitz. We are advising farmers as follows: Although you have some flexibility, it’s not much. Yes, you can grow your usual crop or adapt to the market, but not in all crops. Truth be told, not in most crops. … I object to this amendment because of that.”

In the end, fairness to non-program fruit and vegetable growers took precedence over flexibility. The administration, the Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association, the United Fruit and Vegetable Association, the Western Growers Association, the American Farm Bureau Federation, the National Potato Council, and the majority and minority members of the agriculture committee all backed the amendment.

In his closing remarks, Cohen emphasized the unfairness of allowing program farmers to experiment with growing fruits and vegetables (and to be in direct competition with non-program fruit and vegetable growers), as well as the unfairness of providing those program farmers with a safety net should their foray into fruits and vegetables not prove, well, fruitful.

“Cohen urged lawmakers not to make Maine farmers sit idly by as their rivals—whom they are subsidizing with tax dollars—enter the market and compete for a piece of the action before returning to their full acreage protection.

“The only thing we are trying to convey with this amendment is that if you want to enter the market and want flexibility, you cannot expect a guarantee. We are arguing that it is impossible to leave the security of the federal government’s security program and then return to the volatile market. We don’t have a safety net for growers of other fruits and vegetables or of potatoes in Maine.” See more about Is Lebanese Food Healthy

Fruits Or Vegetables That Have No Health Benefits, Not Dangerous, Just Empty Of Any Observed Benefit

Iceberg lettuce and celery were supposedly pretty useless when I was growing up, and it seems that this cultural perception has persisted.

It’s not really true, though, for two reasons:

Before we fully understood vitamin K, which they both have in good amounts but is still less than some of their leafy cousins, they were both considered to be useless vegetables.

And second, we held that opinion prior to conducting in-depth research on phytonutrients like polyphenols.

Since phytonutrients aren’t vitamins or minerals, it took us some time to investigate them, but in the last 30 years, we’ve found that they have a variety of positive health effects. Some even have the ability to snuff out cancerous cells at the DNA level.

They are typically a part of the plant’s defense mechanism against insects and the environment, so they are present in ALL fruits and vegetables on a generally speaking, albeit minor, basis. They also impart color to them.

These phytonutrients are what define certain foods as “superfoods,” such as blueberries. If you only considered blueberries’ vitamin and mineral content, they wouldn’t be much better than iceberg lettuce.

To answer your question, all fruits and vegetables have some value, though some are undoubtedly more valuable than others.

If that was helpful, kindly follow me so that I might be of further assistance in the future!

If Subsidies For Starchy Foods Were Switched To Those For Fruits And Vegetables

Why not reform the EBT/SNAP credit system instead of subsidizing the growers? Starchy foods aren’t nearly as bad for you as soda, cookies, cakes, candies, kid cereals, etc.

Unless they are improperly prepared, foods like rice, barley, slow-cooked oats, kidney beans, and potatoes are all healthy, satiating, and nutritious. Although it’s irrelevant, I’d like to see stores carry finely milled buckwheat flour as well.

Do you want lower-income Americans to be healthier? Put all prepared snacks in the same category as hot foods: If you want a treat, you must make it from scratch or from a recipe; this rule applies to all candy items as well. EBT food credit is NOT allowed. It’s finally happening, and it’s been overdue for a while.

Is It Appropriate For Governments To Provide Low-income Families With Car Subsidies?

What policy goal are you pursuing really does depend on that

Generally speaking, cars are not as necessary for survival as, say, food, shelter, or health care (all of which are currently subsidized in some way, at least in the US).

Since most jobs require working outside the home, let’s address the issue of transportation if your goal is to find employment. For people who live in cities, public transportation might be a good choice. Government-provided transportation may be sufficient to assist low-income residents in finding employment if it includes buses, trains, and subways (which is what most cities provide).

Second only to purchasing a home in terms of major expenditures for most people, cars themselves. The cost of buying a car is only one part of the overall expense; other costs include fuel, parking (if necessary), insurance, maintenance, and registration.

A low-income family’s budget will be significantly impacted by the cost of owning and operating a car, even with subsidies. They will be in a better position if they can find a way to work and participate in their community and schools without having a car, perhaps using public transportation.

To put it briefly, I don’t think this situation calls for significant policy adjustments. I would like to see improvements in public transportation. On a local level, that is being done.

I’m at a loss for real solutions for rural families. You probably need a car if the closest store is 15 miles away and your neighborhood is on a dirt road.

Why Are Fruits And Vegetables, Which Are Considered To Be Healthy Foods, So Expensive?

There are numerous explanations.

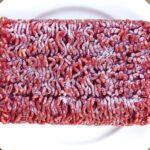

First, less expensive materials are used to create unhealthy foods. The main ingredients in a potato chip or Frito are oil, potato, or corn. Compared to corn or potatoes, a peach or green pepper costs more to grow and harvest.

Second, fresh food is flimsy and spoils quickly. It must be carefully picked at the proper time, packed, and transported in refrigerated trucks. Once it reaches the supermarket, it must be sold shortly after arrival. As you might expect, this involves some effort, expense, and food waste (and consequently has in many places given rise to dumpster diving). In contrast, once potatoes or corn are made into chips, you have a product that is extremely stable, doesn’t need special handling, and stays “fresh” for months.

Third, consumers are accustomed to “pretty” produce. We cherry-pick our produce at the grocery store, so there is not only more waste, but also a lot of the crop is pre-screened and kept from even reaching the average consumer, and is instead sold cheaply (sometimes for animal feed), just composted, or destroyed. (Consider the relatively recent ugly/imperfect food movement, which aims to provide consumers with perfectly healthy but aesthetically flawed produce.) Contrarily, the level of sorting done at the factory for the ingredients that go into pre-processed food is nowhere close to the same.

Produce is not always expensive, though. Seasonal produce can be purchased at a discount, particularly at ethnic markets or right before they close. Local produce is either given away for free to the community or sold at a low price in farming areas. Here in northern California, coworkers who have fruit trees frequently bring in a bag or two of lemons or plums when they are in season and leave them in the break room for anyone to take. The fruit is not at all pretty: the lemons can be very oddly shaped, with thick rinds and sometimes those little black flecks, and the plums are tiny and liberally attended by ants (and spiders). But it’s absolutely delicious, free, and pesticide-free!

Therefore, you might be able to find free or inexpensive produce close to you, but it probably won’t be at the big-box grocery store, and it won’t be the picture-perfect fruit we’ve been brainwashed to expect and want (unless, of course, you’re dumpster-diving, which I’m not qualified to comment on).

The End

Food stamps are a federal program that the government uses to subsidize food for those in need, as other commenters have noted. However, the majority of farm subsidies go to grain farmers; very few go to growers of fruits and vegetables. This is a result of political power, not of any deliberate policymaking.

Giving food stamp recipients some nutrition education would probably be beneficial. Junk food, which is high in fat, sugar, and salt, is appealing and affordable. Perhaps educating home cooks on the benefits of fruits and vegetables and the detrimental effects of sugar-sweetened beverages could be helpful.

To find out more about our healthiest foods, get in touch with us right away.